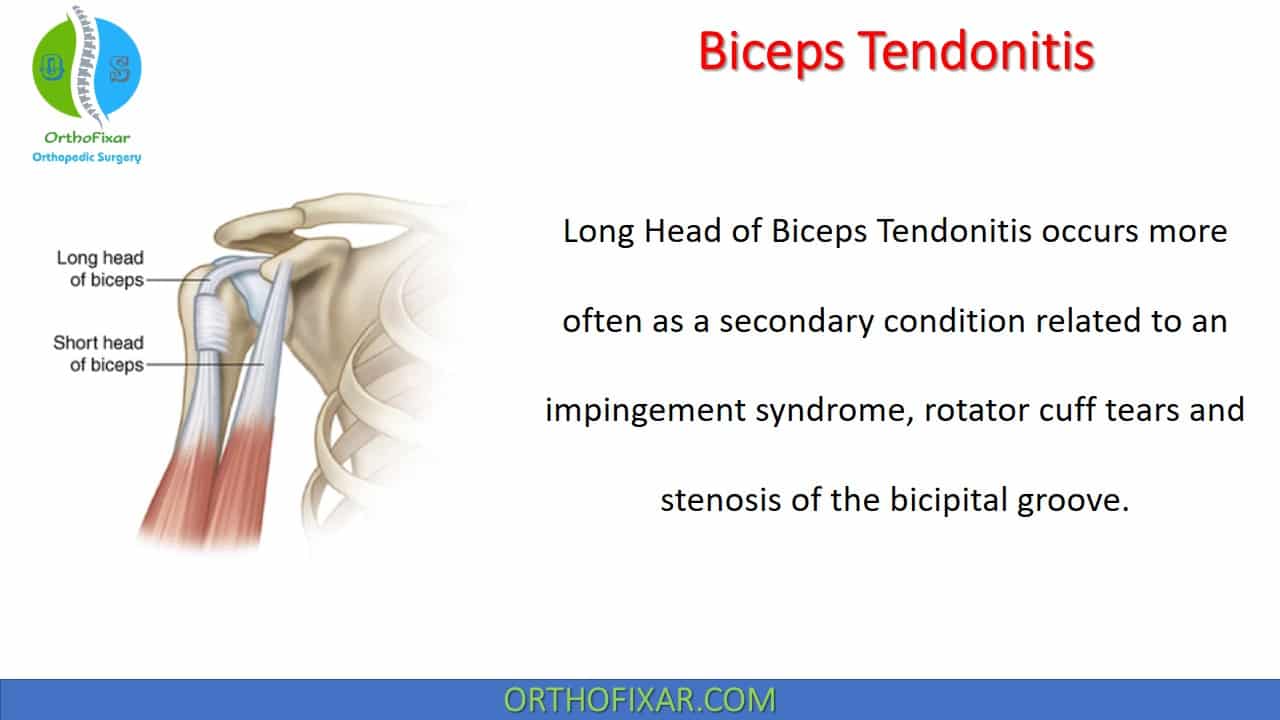

Biceps Tendonitis

Long Head of Biceps Tendonitis occurs more often as a secondary condition related to an impingement syndrome, rotator cuff tears and stenosis of the bicipital groove.

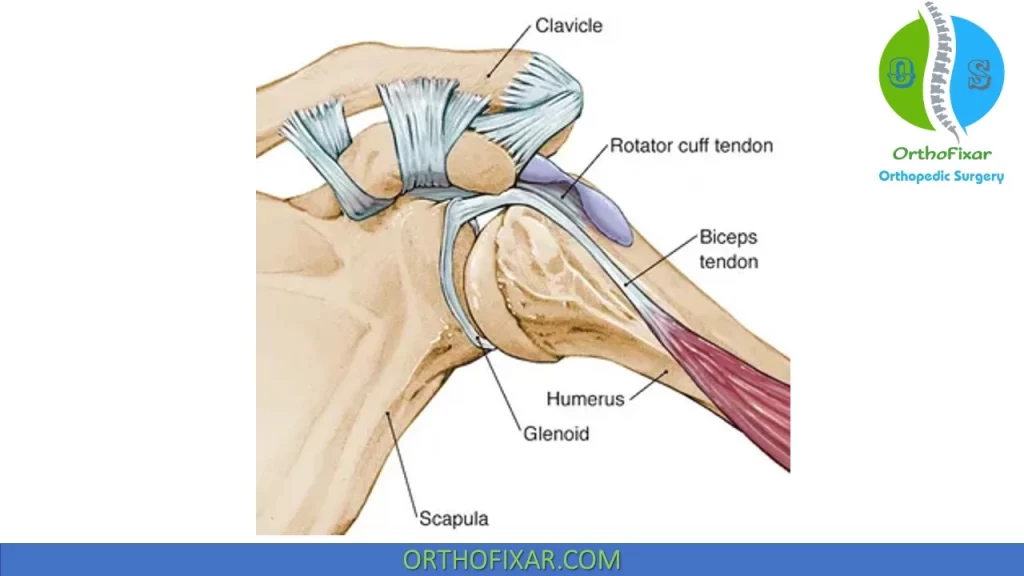

Related Anatomy

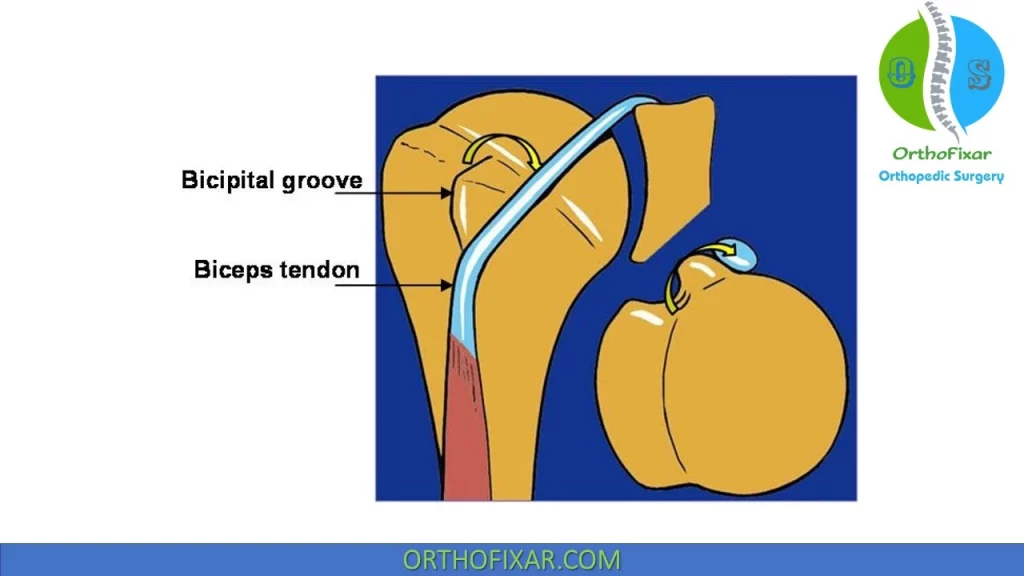

Long Head of Biceps Tendon originates from the supraglenoid tubercle and superior labrum of the shoulder joint. It’s stabilized within bicipital groove by the transverse humeral ligament.

Long Head of Biceps Tendon acts as a dynamic stabilizer of the humeral head.

The biceps tendon sheath is a direct extension of the G-H joint, and inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis can involve the biceps tendon.

See Also: Rotator Cuff of the Shoulder

Biceps Tendonitis Causes

Inflammation of the LHB tendon most often occurs secondarily as a result of surrounding pathologies such as impingement syndrome, pulley lesions, and/or degenerative rotator cuff tears.

Primary LHB tendonitis, in which there is isolated inflammation with no apparent cause, is not uncommon in clinical practice. Although isolated inflammation of the proximal LHB tendon can occur in overhead athletes, this may be the result of repetitive microtrauma as the tendon glides back and forth in a “sawing” motion within the bicipital groove and across the biceps reflection pulley. It is important to remember that because the LHB tendon is encased with synovium, inflammation within the shoulder may track proximally into the biceps-labral complex or distally into the bicipital groove.

Subacromial impingement is the most common mechanism by which LHB tendonitis occurs, especially in older patients. Subcoracoid impingement can also lead to injury involving the LHB tendon and the biceps reflection pulley.

Weak rotator cuff and periscapular musculature potentially allow increased translation of the humeral head, narrowing the space available for the subacromial or subcoracoid contents to pass thus allowing impingement of these structures between the greater tuberosity and the undersurface of the acromion or between the lesser tuberosity and the coracoid.

In patients with subacromial impingement, LHB tendonitis almost always occurs simultaneously since the LHB is subject to the same mechanical wear from the coracoacromial arch. In addition, because the LHB tendon is encased in an outward-facing synovial membrane extending from the glenohumeral joint, any inflammatory process within the joint can thus involve the LHB tendon, producing painful inflammation and tenosynovitis.

LHB tendonitis Stages

- Stage I: The acute stage of LHB tendonitis is characterized by significant anterior shoulder pain localized within the bicipital groove. The LHB tendon will swell and sometimes develop partial thickness tearing at points of maximal wear.

- Stage II: the tendon further degenerates and may form adhesions with surrounding structures such as the bicipital sheath and rotator interval structures. In this stage, microscopic examination reveals fibrinoid necrosis and atrophy of collagen fibers.

- Stage III: As the tendon degenerates, it can either become hypertrophic or atrophic with a deterioration of its organization and infrastructure. If, or when, rupture occurs, symptoms will often resolve immediately with the formation of a “Popeye” deformity. On the contrary, attritional tendon degeneration may occur asymptomatically and painless rupture may occur.

Classification

Slatis and Aalto described a three-part classification for biceps lesions:

- Type A: Impingement tendinitis, which occurs secondary to impingement syndrome and rotator cuff disease. Since the tendon passes beneath the anterior edge of the acromion, impingement can cause biceps tendinopathy as well as rotator cuff problems.

- Type B: A subluxation of the biceps tendon.

- Type C: Attrition tendinitis, commonly associated with spurring and fraying.

Other researchers have proposed two main categories related to age:

- Younger patients developing problems due to repetitive trauma and anomalies of the bicipital groove,

- The older age group developing problems associated with degenerative changes in the tendon.

Biceps Tendonitis Symptoms

The pain associated with Biceps Tendonitis is typically felt along the anterior lateral aspect of the shoulder with radiation into the biceps muscle, and tenderness is noted directly over the bicipital groove. this type of pain is difficult to differentiate from pain related to the anterosuperior cuff which inserts in the area of the bicipital sheath.

Objective findings for this condition include the following:

- Full AROM and PROM, although pain is often reported at the end range of flexion and abduction.

- Normal accessory glides at the G-H joint (negating the need to use joint mobilizations).

- Pain on palpation of the bicipital groove while the arm is positioned at 10 degrees of internal rotation.

- Pain with resisted elbow flexion or resisted forward flexion of the shoulder.

- Pain on passive stretch of the biceps tendon.

- Positive Speed’s test and Yergason test.

Every attempt must be made to identify associated lesions (those affecting the glenoid labrum and rotator cuff) or to note any contributing factors (a poorly stabilized scapular, the hypomobile cervical and/or thoracic spine, or altered muscle recruitment patterns).

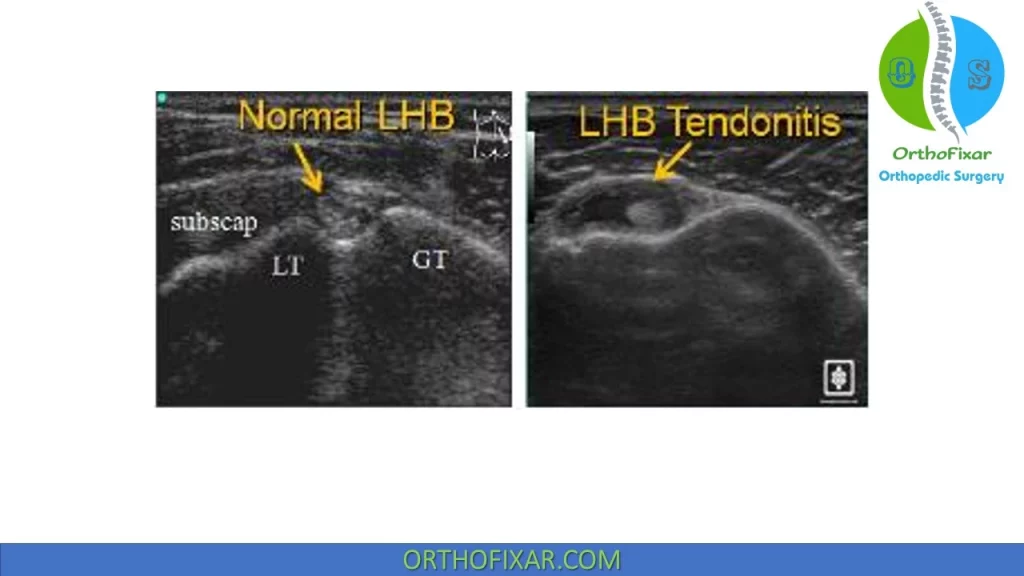

Radiology

Ultrasound imaging can show a thickened tendon within bicipital groove.

MRI can show thickening and tenosynovitis of proximal biceps tendon.

Biceps Tendonitis Treatment

Conservative Treatment:

The Biceps Tendonitis treatment secondary to chronic impingement is similar to that described for rotator cuff tendinitis. These include:

- electrotherapeutic modalities,

- NSAIDs,

- gentle stretching of the contractile tissues.

- local corticosteroid injection (around but not into the tendon).

Surgical Treatment

Biceps Tendonitis Surgical release (with or without Biceps tenodesis) is usually reserved for refractory cases.

Tenotomy without tenodesis is associated with subjective cramping and potential for cosmetic deformity (“Popeye deformity”). Weakness is not associated with tenotomy.

Tenodesis may result in “groove pain” if the technique of the tenodesis retains portion of the tendon in the intertubercular groove.

A subpectoral tenodesis technique reduces the risk of groove pain.

Biceps Tendon Subluxation

The Long Head of Biceps tendon, with its proximal point of exit at a 30–40 degree angle from the straight line of the tendon and the tunnel, swings from one side of the groove to the other during the motions of IR and ER of the humerus.

Biceps Tendon Subluxation is most commonly associated with a partial or complete subscapularis tear.

If the groove is shallow: the tendon may force its way over the lesser or greater tuberosity, tearing the transverse humeral ligament in the process. Repeated subluxation wears down the tuberosity and increases the frequency of the subluxation.

If the groove is narrow and tight: the constant pressure of the tendon has the potential to cause tendinitis or even rupture of the tendon.

Symptoms:

The pain, not often severe, has the same referral pattern as that of Biceps Tendonitis.

A click is typically felt during abduction and ER motions, with reduction of the tendon occurring with adduction and IR.

There is tenderness over the bicipital groove, which follows the groove as the arm is rotated.

On IR, the groove is under the coracoid, and during ER it is at the anteromedial line.

Treatment:

The Biceps Tendon Subluxation treatment depends largely on how important athletics is to the participant.

Conservative treatment involves the temporary avoidance of the pain and click-provoking movements.

In severe cases, surgical intervention may be indicated, which offers excellent results.

Operative treatment includes:

- repair of the subscapularis and supporting structures of the bicipital groove.

- more often involves tenotomy or tenodesis with or without a subscapularis repair.

Long Head of Biceps Tendon Tear

The Long Head of Biceps Tendon Tear is usually seen in middle-aged patients, resulting from repeated injections of steroid into the bicipital groove or in cases of chronic impingement.

The tendon is avascular, and as it weakens, it tears with a minimal amount of force.

Patients usually report hearing or feeling a “snap” at the time of the injury.

Typically, rupture is followed by a few weeks of mild-to-moderate pain, followed by resolution of the pain and restoration of normal function.

When attempts are made to contract the biceps, the muscle belly rolls down over the distal humerus, producing a swelling close to the elbow instead of in the middle of the arm: the so-called ” Popeye sign”.

Functional limitations are unusual after this rupture, especially in the older population, because the short head of the biceps remains intact. Typically, there is a negligible loss of elbow flexion and supination strength.

Surgical repair is rarely indicated except in the younger, active population (<50 years).

With or without surgery, a rupture of the LHB increases the risk of developing an supraspinatus impingement syndrome. This results from the short head of the biceps pulling the humeral head upward, without the presence of the long head to hold the humeral head downward.

References

- Neviaser RJ. Painful conditions affecting the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983 Mar;(173):63-9. PMID: 6825347.

- Neviaser TJ: The role of the biceps tendon in the impingement syndrome. Orthop Clin North Am 18:383–386, 1987.

- Slatis P, Aalto K: Medial dislocation of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica 50:73–77, 1979.

- De Palma AF: Bicipital tenosynovitis. Surg Clin North Am 22:1693–1702, 1953.

- Warren RF: Lesions of the long head of the biceps tendon. Instr Course Lect 34:204–209, 1985.

- O’Donoghue DH: Subluxing biceps tendon in the athlete. Clin Orthop 164:26–29, 1982.

- Chepeha JC: Shoulder trauma and hypomobility. In: Magee DJ, Zachazewski JE, Quillen WS, eds. Pathology and Intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. St. Louis, MI: Saunders, 2009:92–124

- Daigneault J, Cooney LM Jr: Shoulder pain in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 46:1144–1151, 1998.

- Dutton’s Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, And Intervention 3rd Edition.

- Millers Review of Orthopaedics -7th Edition Book.

- Lifetime product updates

- Install on one device

- Lifetime product support

- Lifetime product updates

- Install on one device

- Lifetime product support

- Lifetime product updates

- Install on one device

- Lifetime product support

- Lifetime product updates

- Install on one device

- Lifetime product support