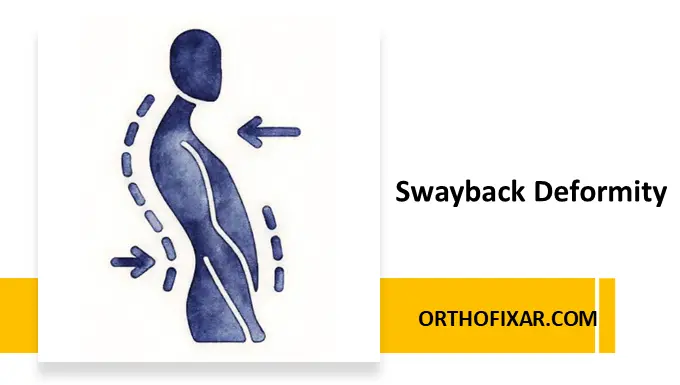

Swayback deformity is a postural deviation characterized by abnormal sagittal plane alignment involving the pelvis, lumbar spine, and thoracic spine. Unlike simple hyperlordosis, swayback posture represents a global postural adaptation in which multiple body segments shift to maintain balance and center of gravity. This deformity is commonly observed in adolescents and adults with prolonged standing habits, muscle imbalance, or poor postural control.

Postural Description of Swayback Deformity

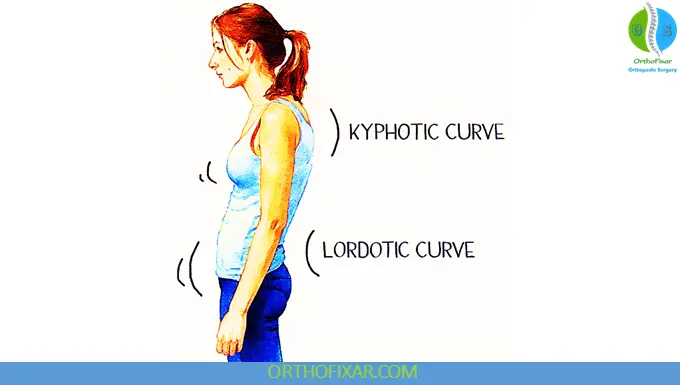

In swayback deformity, there is an increased pelvic inclination of approximately 40°, combined with a thoracolumbar kyphosis. The spine bends sharply backward at the lumbosacral junction, creating a characteristic posterior trunk displacement relative to the pelvis.

Key postural features include:

- Anterior translation of the pelvis, making it the most anterior body segment

- Hip joints positioned in extension

- Thoracic spine flexion occurring as a compensatory mechanism to maintain the center of gravity

- Increased thoracic and lumbar curves, despite flattening of the lower lumbar region

To compensate for these structural shifts, the thoracic spine becomes more mobile, flexing on the lumbar spine to preserve upright posture.

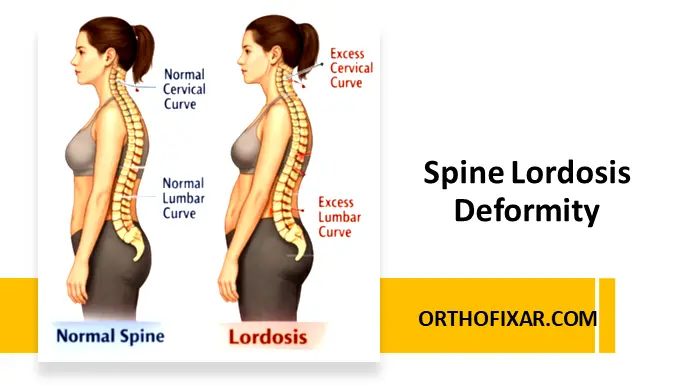

See Also: Spine Lordosis Deformity

Biomechanical and Muscular Imbalance

Swayback deformity is primarily a result of muscle imbalance, where certain muscle groups become chronically shortened while others are elongated and weak.

Commonly Elongated and Weak Muscles

- One-joint hip flexors

- Lower abdominals

- External obliques

- Lower thoracic extensors

- Neck flexors

- Gluteus medius (especially posterior fibers) on the favored leg in unilateral stance

These weaknesses contribute to poor pelvic control, reduced trunk stability, and increased reliance on passive structures.

Commonly Shortened and Strong Muscles

- Hamstrings

- Hip extensors

- Upper fibers of the internal obliques

- Internal intercostals

- Low back musculature (shortened but not functionally strong)

- On the favored side: Tensor fascia lata with a tight iliotibial band

This pattern promotes posterior pelvic positioning and reinforces abnormal loading through the lumbar spine and hips.

Segmental Alignment Changes in Swayback Deformity

| Body Segment | Alignment Changes |

|---|---|

| Spine | Long thoracic kyphosis with compensatory mobility |

| Lumbar Spine | Flattened lower lumbar region |

| Pelvis | Neutral or posterior tilt with anterior translation |

| Hips | Positioned anterior to posture line; hyperextended |

| Knees | Hyperextension common |

| Weight Bearing | Predominantly on one leg |

| Pelvic Obliquity | Pelvis drops toward non-favored side |

| Apparent Limb Length | Favored leg appears longer in standing only |

Joints Commonly Affected

Due to altered alignment and abnormal loading, swayback deformity frequently affects multiple joints, including:

- Lumbar spine

- Pelvic joints

- Hip joints

- Thoracic spine

- Scapulothoracic joint

- Glenohumeral joints

- Cervical spine

- Atlanto-occipital joints

- Temporomandibular joints

These joint stresses may contribute to chronic pain syndromes, fatigue, and reduced functional efficiency.

Clinical Relevance

From a clinical perspective, swayback deformity should not be viewed as an isolated spinal issue but rather as a whole-body postural dysfunction. Patients may present with:

- Low back pain

- Hip or groin discomfort

- Thoracic stiffness

- Neck strain or headaches

- Early fatigue during prolonged standing

Accurate identification of muscle length–strength relationships is critical before initiating corrective exercise or manual therapy.

Conclusion

Swayback deformity represents a complex interaction between skeletal alignment, muscle imbalance, and compensatory movement strategies. Effective management requires a comprehensive postural assessment and a targeted rehabilitation approach focused on restoring muscular balance, improving postural awareness, and optimizing load distribution across the spine and lower extremities.

Early recognition and intervention can significantly reduce the risk of chronic pain and long-term musculoskeletal dysfunction.

References & More

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders. Pubmed

- Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic Exercise: Foundations and Techniques. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1985.

- Orthopedic Physical Assessment by David J. Magee, 7th Edition.

Closed.