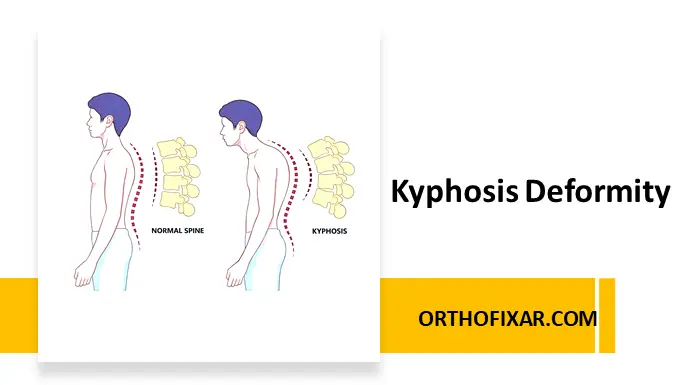

Kyphosis is defined as a posterior curvature of the spine, most commonly involving the thoracic spine. While a mild thoracic kyphotic curve is physiologically normal, pathological kyphosis represents an exaggeration of this curve and may lead to functional impairment, pain, and cosmetic deformity.

Pathological kyphosis can develop at any age and may be structural or postural in nature, depending on the underlying cause.

Causes of Kyphosis

Kyphosis may result from a wide range of congenital, developmental, pathological, and degenerative conditions, including:

- Vertebral compression fractures

- Tuberculosis of the spine

- Scheuermann’s disease (vertebral osteochondritis)

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Senile osteoporosis

- Spinal tumors

- Congenital vertebral anomalies

- Compensatory changes associated with lordosis

- Neuromuscular paralysis leading to loss of postural control

See Also: Swayback Deformity

Congenital Causes

Congenital kyphosis may result from:

- Partial segmental defects (e.g., osseous metaplasia)

- Vertebral centrum hypoplasia or aplasia

These anomalies alter normal vertebral development, leading to fixed structural deformity.

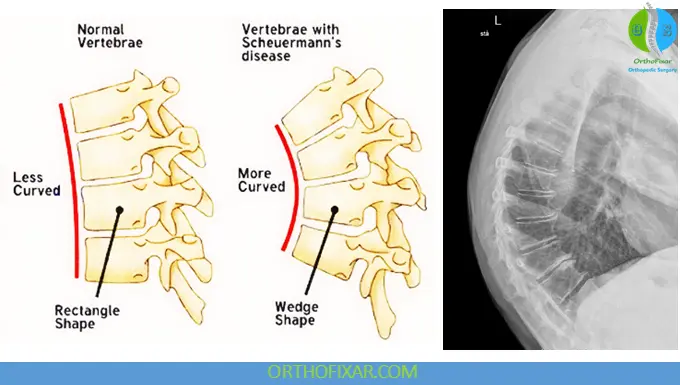

Scheuermann’s Disease and Structural Kyphosis

Scheuermann’s vertebral osteochondritis is a common cause of structural kyphosis. It is a growth disorder affecting approximately 10% of the population.

Key Features:

- Inflammation of bone and cartilage around the vertebral ring epiphysis

- Anterior wedging of vertebral bodies

- Typically involves multiple vertebrae

- Most commonly affects the T10–L2 region

This condition often presents during adolescence and results in a rigid thoracic kyphosis.

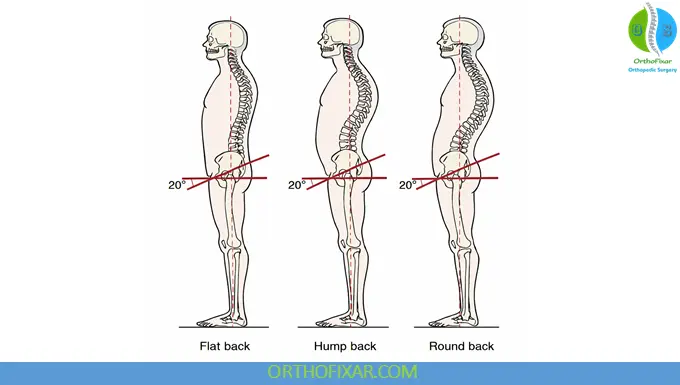

Types of Kyphosis

Kyphosis deformities are commonly classified into four main types, based on posture, structure, and clinical presentation.

1. Round Back Kyphosis

Round back is characterized by a long, smooth thoracolumbar kyphotic curve.

Postural Characteristics:

- Decreased pelvic inclination (<30°)

- Increased thoracolumbar kyphosis

- Forward-flexed trunk posture

- Decreased lumbar lordosis

Muscle Imbalances:

- Tight muscles:

- Hip extensors

- Trunk flexors

- Weak muscles:

- Hip flexors

- Lumbar extensors

This form is often postural and may respond well to rehabilitation.

Postural Changes Associated with Round Back Kyphosis

Body Segment Alignment

- Head held forward with cervical hyperextension

- Protracted scapulae

- Increased thoracic kyphosis

- Flexed hips and hyperextended knees

- Head is typically the most anteriorly displaced body segment

Muscles Commonly Elongated and Weak

- Neck flexors

- Upper thoracic erector spinae

- External obliques

- Middle and lower trapezius (when scapulae are protracted)

- Thoracic erector spinae

- Rhomboids

Muscles Commonly Short and Strong

- Neck extensors

- Hip flexors

- Serratus anterior

- Pectoralis major and minor

- Upper trapezius

- Levator scapulae

- Upper abdominal muscles

- Intercostal muscles

Joints Commonly Affected

- Thoracic spine

- Scapulothoracic joints

- Glenohumeral joints

2. Humpback (Gibbus Deformity)

Humpback, also referred to as gibbus deformity, presents as a localized, sharp posterior angulation of the thoracic spine.

Key Points:

- Usually structural and rigid

- Commonly caused by vertebral fractures or pathological conditions

- Prominent angular deformity visible on inspection

3. Flat Back Kyphosis

A patient with flat back demonstrates a reduction in normal spinal curves.

Characteristics:

- Pelvic inclination decreased to approximately 20°

- Reduced lumbar lordosis

- Mobile lumbar spine

- Altered sagittal balance

This posture may result in fatigue and difficulty maintaining upright posture.

Changes Associated with a Flat Back Form of Kyphosis

Body segment alignment

- Loss of lordosis with pelvis in posterior tilt

- Hip and knee joints hyperextended

- Forward head posture with increased flexion to upper thoracic spine

Muscles commonly elongated and weak

- One joint hip flexors

- Lumbar extensors

- Local stabilizers (multifidus, rotators)

- Scapular protractors

- Anterior intercostals

Muscles commonly short and strong

- Hamstrings

- Abdominals may be strong with back muscles slightly elongated

- Hip extensorsScapular retractors

- Thoracic erector spinae

Joints commonly affected

- Lumbar spine

- Pelvic joints Scapulothoracic joints

- Thoracic spine

- Cervical spine

4. Dowager’s Hump

Dowager’s hump is most commonly seen in elderly individuals, particularly women.

Cause:

- Osteoporosis leading to degeneration and anterior wedging of thoracic vertebral bodies

Clinical Features:

- Progressive thoracic kyphosis

- Height loss

- Increased fracture risk

Kypholordotic Posture

In some individuals, both the thoracic and lumbar regions are affected, resulting in a kypholordotic posture.

Features:

- Increased thoracic kyphosis

- Compensatory increase in lumbar lordosis

- Altered pelvic alignment

- Increased stress on spinal structures

This combined deformity significantly affects global posture and spinal biomechanics.

Changes Associated with Kypholordotic Posture

Body segment alignment

- Head held forward withcervical spine hyperextended

- Scapulae may be protracted

- Increased lumbar lordosis, and increased thoracic kyphosis

- Pelvis anteriorly tilted Hip flexed, knee hyperextended

- Head is usually most anteriorlyplaced body segment

Muscles commonly elongated and weak

- Neck flexors

- Upper erector spinae

- External obliques

- If scapulae are protracted, middle and lower trapezius

- Thoracic erector spinae

- Middle and lower trapezius

- Rhomboids

Muscles commonly short and strong

- Neck extensors

- Hip flexors

- If scapulae are protracted, serratus anterior, pectoralis major and/or minor, upper trapezius

- Intercostals

Joints commonly affected

- Thoracic spine

- Lumbar spine

- Scapulothoracic joints

- Glenohumeral joints

Clinical Importance of Kyphosis Assessment

Early identification of kyphosis is essential to:

- Prevent progression

- Reduce pain and functional limitations

- Improve posture and respiratory mechanics

- Guide appropriate conservative or surgical management

A thorough postural, muscular, and radiographic assessment is critical in determining the type and severity of kyphosis.

Kyphosis Treatment

The management of kyphosis depends on the type, severity, age of the patient, flexibility of the curve, and underlying cause. Treatment goals focus on pain reduction, postural correction, functional improvement, and prevention of progression.

Conservative (Non-Surgical) Treatment

Conservative management is the first-line approach for most postural and mild structural kyphosis cases.

- Postural education and ergonomic correction

Training patients to maintain neutral spinal alignment during daily activities. - Physical therapy and corrective exercise programs

- Strengthening weak muscles (thoracic extensors, lumbar extensors, scapular stabilizers)

- Stretching shortened structures (hip flexors, pectoral muscles, cervical extensors)

- Spinal mobility and stabilization exercises

- Bracing (in selected cases)

- Commonly used in adolescents with progressive Scheuermann’s kyphosis

- Most effective before skeletal maturity

- Pain management

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Activity modification

- Osteoporosis management (when indicated)

- Calcium and vitamin D supplementation

- Pharmacologic therapy to reduce fracture risk

Surgical Treatment

Surgical intervention is reserved for severe or progressive cases and is considered when conservative treatment fails.

Indications may include:

- Severe kyphotic deformity with significant functional limitation

- Neurological compromise

- Progressive deformity

- Intractable pain

- Structural deformity such as severe Scheuermann’s disease or vertebral collapse

Surgical goals include:

- Correction of spinal alignment

- Stabilization of the affected spinal segments

- Decompression of neural structures when necessary

Prognosis and Follow-Up

- Postural kyphosis generally has an excellent prognosis with early intervention and adherence to rehabilitation.

- Structural kyphosis requires long-term monitoring and individualized management.

- Regular follow-up is essential to monitor curve progression, functional status, and treatment response.

Key Clinical Takeaway

Early diagnosis, appropriate classification, and a multidisciplinary treatment approach are critical in achieving optimal outcomes for patients with kyphosis deformity.

References & More

- Orthopedic Physical Assessment by David J. Magee, 7th Edition.

- Moe JH, Bradford DS, Winter RB, et al. Scoliosis and Other Spinal Deformities. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1978.

- McMorris RO. Faulty postures. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1961;8:213–224.

- Tsou PM. Embryology and congenital kyphosis. Clin Orthop. 1977;128:18–25

- White AA, Panjabi MM, Thomas CC. The clinical biomechanics of kyphotic deformities. Clin Orthop. 1977;128:8–17. Pubmed

- Hensinger RN. Kyphosis secondary to skeletal dysplasias and metabolic disease. Clin Orthop. 1977;128:113–128. Pubmed

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK: Muscles: testing and function, Baltimore, 1983, Williams & Wilkins; Giallonardo LM: Posture. In Myers RS, editor: Saunders manual of physical therapy practice, Philadelphia, 1995, WB Saunders. Pubmed